The NHL Draft is just under a month away. The draft always provides plenty of drama and intrigue amongst fans and media. This has been true since the inception of the draft. While people tend to get excited about trades and prospects, there are other moments that leave people scratching their heads. In this draft story, we head back to 1983 when one of the league’s first expansion teams had fallen on hard times. This story has attempted relocation, lawsuits, countersuits, potential contraction, and a team that was in such turmoil, that it refused to participate in the draft.

NHL Draft Stories: The Saskatoon Blues

Expansion Darlings

In 1967-68 the NHL expanded to twelve teams. Among those teams was the St. Louis Blues. Like most of their expansions cousins, they initially struggled to gain footing in their new sports landscape. However, the early success of the team brought the fans in. The Blues made the Stanley Cup Finals in their first three years. While much of that had to do with the playoff format, it was still enough of an accomplishment to, seemingly, solidify the Blues in the St Louis sports landscape.

In fact, the Blues made the playoffs in nine of their first 10 seasons. Coupled with the on-ice success, the Blues owners Sidney Salomon Jr. and his son Sid the third were considered great owners, especially by their players. The Salmons would pay their players higher salaries than other teams and go out of their way to make the players feel appreciated when they performed well. The relationship between the owners and players was highlighted in a 1969 Sports Illustrated article. “The Salomon’s tender loving care notoriously extends to the Blues players. Any man who does something to enhance the team’s name – scores three goals in a game, makes the All-Star team, plays a major role in a key victory – gets a gold wristwatch. Not any gold wristwatch, mind you, but a $750 Patek Philippe.”

Not So Perfect

Everything seemed to be going perfectly for the Blues. The team went to three consecutive Cup Finals and attendance was at 100%. So when Solomon the third said in a 1970 interview: “They say we got [the franchise] for $2 million, a bargain. But remember this, we spent another $8 million for our building and improvements. That’s a big investment. We don’t know if we’ll be able to compete well enough in the future to make it pay off.” it raised a few eyebrows. On the surface, the Blues seemed to be a model franchise however, below the surface cracks were starting to form. While the public was largely unaware of the Solomons’s concerns, the affair was made rather public in July of 1975.

Letter To the Mayor

The Solomon’s had been lobbying politicians for the right to build a new 1,000-spot parking lot across from the St Louis Arena in Forrest Park. The proposal was met with strong criticism over the environmental impact and the plans were withdrawn.

In response to the parking lot deal falling apart, the Solomon’s wrote a letter to the Mayor of St Louis, John Poelker. The latter outlined all the difficulties the owners encountered presenting NHL hockey in the city of St. Louis. The letter was later published in the St Louis Post Dispatch for all to see. The letter outlined the difficulties maintaining the St Louis Arena as well as other difficulties with the State and Municipal Governments.

The St Louis Arena

St Louis was awarded the team because Chicago Blackhawks owner Arthur Wirtz backed it. Wertz was part owner of the St Louis Arena. With the arena aging and neglected, Wirtz was looking to unload the property and saw an opportunity. Wertz backed the St Louis bid so he could offload the arena to the Solomon’s. So along with the $10,000 application fee and the $2 million expansion fee, the Solomon’s also paid $4 million to acquire the St Louis Arena from Wirtz.

In 1977, Ralston Purina buys the St. Louis Blues of the National Hockey League, as well as the St. Louis Arena. The facility soon becomes known as the Checkerdome and features the familiar Checkerboard logo. The Blues and the arena were sold to Harry Ornest in 1983. #Purina125 pic.twitter.com/ZDEFwe6oiJ

— Lisa Kelly #LoveTheeND 💗☘️🏈 (@4LeafCloverGirl) January 29, 2019

The Solomon’s had to sink another $2 million into the ‘Old Barn’ just to make it a suitable NHL arena for the Blues’ inaugural season. Between 1967 to 1975 the Solomons invested another $5 million into the arena for improvements, such as expanding seating capacity. Beyond the investments made to improve the arena, the annual maintenance cost was also extremely high. Finally, the arena was not air-conditioned, so it could only run seven months a year despite having to pay fixed annual costs to run and maintain the building.

Issues With the City and State

Most NHL teams paid (at that time) 4.5% in tax to the city and state. The Blues had the highest tax rate in the league at 9.5%. The Solomons wanted some kind of tax relief to help with the burden of tax payments which had cost the Solomons $5 million dollars between 1968 to 1975.

The city-operated Kiel Auditorium competed with the St Louis Arena for concerts and events. Since The Kiel Auditorium was run by the government, it could operate at a significant loss. Municipal taxpayers would subsidize the arena’s losses to keep it operational. Therefore, they could charge significantly lower rent to attract the events than the St Louis Arena. With the advantage of the lower rent, Kiel Auditorium consistently won the rights to the events. This left the St Louis Arena mostly unused on non-hockey nights.

Solomon Jr. also felt there was a lack of government support for the Blues. In other cities, the governments promoted and supported the sports teams with preferential rent and tax agreements as well as building new arenas. The Solomons had planned to build a new arena with government support but the plans were rebuffed.

In response to all these issues, the Solomons began making veiled threats to move the team. These threats became more real when in 1976 the Solomon’s were granted the ability to sell or relocate the team by the other NHL owners.

Consequences

The Solomon’s complaining did not sit well with the St Louis faithful, especially when they threaten to move. Things got worse in 1977 when the Blues fired several employees to meet payroll. The only explanation given by the ownership was the increasing financial burden of the arena they had to consolidate several departments. All the turmoil led to a drop in season-ticket sales. Between 1970-71 to 1974-75 the Blues led the league in attendance. Once all the issues were made public, attendance started to drop. Reportedly there was a 5,000 drop in season ticket sales in 1977.

Along with the intention between Blues ownership and the federal and municipal governments, fans were also getting fed up with the poor management of the team. Specifically Sid Solomon III. Sid III became known as a meddler. He constantly fired his coaches and general managers. between 1971 and 1977 the Blues had 11 coaches and six general managers.

Ralston Purina

In 1976 the Blues hired Emile Francis as head coach, general manager and executive vice-president. When all the turmoil in 1977, the ‘cat’ began to work his magic. He somehow convinced H. Hal Dean, chairman of the Ralston, to buy the Blues, the St Louis Arena and the subsequent $8.8 million debt on both entities as a civic responsibility. With new ownership committed to the St Louis market, the turmoil subsided.

It subsided until 1981 when Dean retired and Ralston Purina had a new chairman, Wiliam Stiritz. Stiritz had no interest in hockey or owning a team that was operating at a $10 million loss. In 1982, it was announced Stiritz was putting the Blues up for sale. In a shocking announcement, Stiritz announced the team had been sold to Batoni-Hunter Enterprises, Ltd. a company out of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

Saskatoon Blues

Batoni’s president was Bill Hunter, one of the founders of the WHA and former owner of the Edmonton Oilers (WHA version). Hunter said once the deal was finalized, the team would move to Saskatoon and they were ready to break ground on a new 18,000-seat arena for the new team. Hunter and Ralston had agreed on a price, Ralston then cut 60% of the Blues staff in preparation for the move. All that was needed was the other owner’s approval.

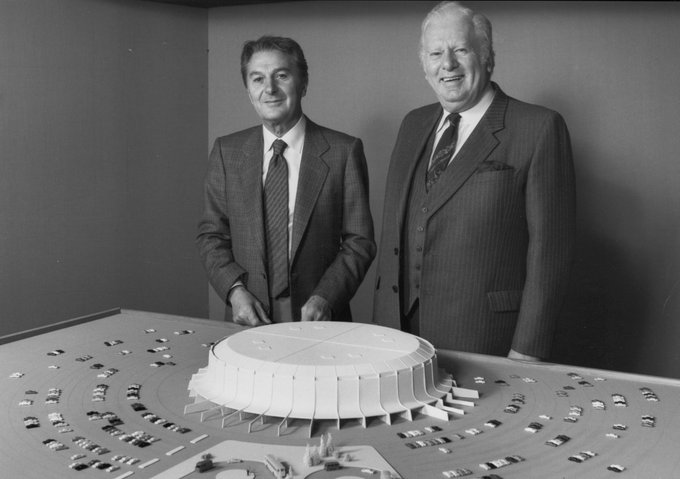

Hmm. Here’s a photo of “Wild” Bill Hunter with developer Peter Batoni in 1983 with a model of the proposed NHL arena that was supposed to become the #Saskatoon home for the Blues. #NHL pic.twitter.com/zC6MOh39D4

— Phil Tank (@thinktankSK) May 22, 2019

Unfortunately for Hunter, the league did not approve the sale. They felt Saskatoon was too small a market for an NHL team. In response, Ralston filed an anti-trust lawsuit against the league, owners, and the NHL president.

To make things worse, Ralston announced: “it had no intention of remaining in the hockey business and no intention of operating the team next year.” Ralson was tendering the team to the league “to operate, sell or otherwise dispose of in whatever manner the league desires.” After the league decides what it is going to do with the Blues, Ralston stated the NHL “to remit any proceeds from a dissolution or sale to the company. If the league decided to operate the team, Ralston expected to receive fair value for the franchise.”

1983 Draft

After the stunning Ralston announcement, what was left of the Blues management team was in limbo. Complicating things was the announcement was made just five days before the 1983 draft. The situation was such a mess that the Blues scouts travelled to Montreal at their own expense after being ignored by Ralston for weeks leading up to the draft. The scouts believed, despite the turmoil and contention between the league and ownership, they would still participate in the draft.

Well, they were wrong. The scouts never heard from ownership. Ralston stated they are not required to participate in the draft, and sent no representatives to the draft. The Blues became the only team to decline to participate in a draft in NHL history. The Blues simply had an empty table in the draft room. Part of the sting of this decision was taken off because the Blue had already traded away their first two picks in the draft. Still, it was quite a statement from the Ralston Purina group even though it would hurt the team. The NHL was understandably unhappy with what it perceived as an owner deliberately trying to make its team worse. This back and forth between the Blues ownership and the league was just heating up.

Fallout

As a result of Ralston’s decision to sit out the draft, the league forced the Blues to forfeit their draft picks and filed a countersuit against Ralston for “damaging the league by willfully, wantonly and maliciously collapsing its St. Louis Blues hockey operation.” Ralston threatened to liquidate the team, which cause the NHLPA to threaten the NHL with a lawsuit. It was getting very messy.

The league ultimately stripped Ralston of the team and took over day-to-day operations. With the league running out of potential buyers, things looked bleak for the Blues. Cue Harry Ornest. He would buy the team and keep them in St Louis. While his times as Blues owner only lasted between 1983 to 1986, before selling the team to a group led by Missouri businessman Mike Shanahan and the arena to the city of St Louis (at a profit). Ornest was not in St Louis long but saved the Blues from contraction and relocation.